In this blog, I set out to illustrate the interconnectedness of the three modes of communication in English; reading and viewing, writing and representing and speaking and listening. Through an exploration of literacy theory, the Tasmanian English-literacy curriculum and my own teaching strategy, I have demonstrated that the three modes are equally important for English teachers and students. Likewise, I have shown that each mode of communication must be used to support teaching of the other modes. An example of this was the activity from the text Once by Morris Gleitzman. Although the activity was primarily a writing task, reading and comprehension, as well as speaking and listening through reading aloud and discussion, were essential to its successful completion. Finally, a brief reflection on my own pedagogy has led to the conclusion that an effective English curriculum must contain all three modes of communication.

Ruth's English literacy blog

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Pedagogical Implications

When planning teaching strategies, I tend always to look at a text from a text level perspective. As can be seen in the activity from my last post, I find it very effective to consider themes and ideas in a text, and the way texts are used to position audiences. These priorities reflect an emphasis in my teaching on the reading and viewing strand of the curriculum. Likewise, I find the text participant role of the four resources model easiest to incorporate into my teaching. I have always enjoyed reading and understanding texts, and appear, as a result, to have prioritised this form of learning for my students. Designing this strategy, however, has demonstrated that reading never really occurs apart from writing, listening and speaking.

Careful study of the curriculum outcomes has also shown that even tasks with a text-level focus naturally incorporate word- and sentence-level learning. When rewriting the events of Once, for example, students need to develop simple, compound and complex sentences and use appropriate vocabulary and punctuation (Department of Education, n.d., p. 110). I am well aware of the importance of grammar and word-level learning in English. I also recognise the need to make this sometimes ‘mundane’ learning relevant to students. As such, I need to ensure that explicit grammar teaching is included when I design broader text studies.

In studying the theory behind the modes of communication and developing a teaching strategy, I have realised that I struggle with the same preconceptions, regarding speaking and listening, as many teachers. Although our society values good orators, the education system prioritises reading and writing as the main literacy indicators. Particularly with the pressures of NAPLAN testing, teaching these areas has taken priority for many teachers (McDougall, 2004; Nixon, 2001). Similarly, my own English background placed significant emphasis on reading and writing, sometimes at the expense of speaking and listening. However, speaking and listening are clearly essential to many of the outcomes embedded in the other two strands. Words like ‘explain’, ‘describe’ and ‘discuss’ which are used extensively in the reading strand of the curriculum (DoE, n.d. pp.61-2), require students to use their speaking and listening skills. Recognition of the relationship between oracy and the more ‘conventional’ literacy skills enables me to better appreciate the importance of classroom and small group discussion in student learning.

Careful study of the curriculum outcomes has also shown that even tasks with a text-level focus naturally incorporate word- and sentence-level learning. When rewriting the events of Once, for example, students need to develop simple, compound and complex sentences and use appropriate vocabulary and punctuation (Department of Education, n.d., p. 110). I am well aware of the importance of grammar and word-level learning in English. I also recognise the need to make this sometimes ‘mundane’ learning relevant to students. As such, I need to ensure that explicit grammar teaching is included when I design broader text studies.

In studying the theory behind the modes of communication and developing a teaching strategy, I have realised that I struggle with the same preconceptions, regarding speaking and listening, as many teachers. Although our society values good orators, the education system prioritises reading and writing as the main literacy indicators. Particularly with the pressures of NAPLAN testing, teaching these areas has taken priority for many teachers (McDougall, 2004; Nixon, 2001). Similarly, my own English background placed significant emphasis on reading and writing, sometimes at the expense of speaking and listening. However, speaking and listening are clearly essential to many of the outcomes embedded in the other two strands. Words like ‘explain’, ‘describe’ and ‘discuss’ which are used extensively in the reading strand of the curriculum (DoE, n.d. pp.61-2), require students to use their speaking and listening skills. Recognition of the relationship between oracy and the more ‘conventional’ literacy skills enables me to better appreciate the importance of classroom and small group discussion in student learning.

References:

Department of Education Tasmania Hobart , Tasmania

McDougall, J. K. (2004). Changing mindsets: A study ofQueensland

Nixon, H. (2001). The book, the TV series, the website…: Teaching and learning within the communicational webs of popular media culture. In 'Leading literate lives: AATE / ALEA joint national conference, Hobart 12-15 July 2001'. Hobart: AATE / ALEA.

McDougall, J. K. (2004). Changing mindsets: A study of

Nixon, H. (2001). The book, the TV series, the website…: Teaching and learning within the communicational webs of popular media culture. In 'Leading literate lives: AATE / ALEA joint national conference, Hobart 12-15 July 2001'. Hobart: AATE / ALEA.

My teaching strategy - Once by Morris Gleitzman

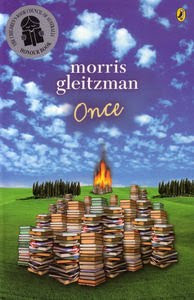

In previous posts, I have considered how literacy theory and the curriculum documents support an unequivocal relationship between the modes of reading and viewing, writing and representing and speaking and listening. I now want to introduce a strategy that contextualises this relationship in teaching practice. This strategy will demonstrate how learning is supported by all three modes of communication. In this strategy, I will use the fictional text Once by Morris Gleitzman.

|

| Picture from Penguin Books |

This strategy will be used in a class of year seven students. Gleitzman’s text is suitable for year sevens because it has a bright, colourful cover, large writing and short chapters. These characteristics increase the text’s interest and appeal for younger students. Although the book deals with some difficult themes, it presents them through the eyes of a child, using simple vocabulary and sentence structure.

The text is written from the perspective of a young orphan situated in Poland

The task in this strategy requires students to recreate an event from chapter 15 of the text. They must do this from the perspective of one of the other characters; the children’s protector Barney, the best friend Zelda, the Nazi officer or a bystander. After reading the chapter, I will lead a class discussion to help students with basic comprehension of the text. Given the structure and themes of this text, the key discussion question, drawn from Wing Jan (2009), is ‘What did I feel as I read?’ (p. 6). This question, which is asked from a text participant perspective, helps students to identify with the characters in the text and engage with their points of view. Again, this element of the strategy illustrates the connection between writing, speaking and listening as taking notes from the discussion will aid learning by informing the written task. When recreating the story from another perspective, students work primarily with the writing and representing strand of the curriculum. As text users, they consider the purpose and audience of their text, and select appropriate language features to create the text (Wing Jan, 2009).

This strategy illustrates the interconnectedness of the three strands of the curriculum by addressing a number of learning outcomes from each. For example, students ‘describe ways in which points of view are presented in texts’ (DoE, n.d., p. 61), ‘select language features to... portray people’ (p. 64), and ‘speak and listen through... discussions in formal and informal contexts’ (p. 68). However, it also illustrates that each of the modes of communication links up with the others to support learning. Listening and speaking in classroom discussions extends learning by enabling students to share and explore information. If students then write the information down, and use it to create new texts, this continues to support and extend learning. These texts are then read, as was the original, and the cycle of learning continues. Effective teaching strategies use all three modes to support learning. I will discuss this further in my next post when I look at the three modes in the context of teaching practice.

References:

Department of Education Tasmania Hobart , Tasmania

Gleitzman, M. (2005). Once. Camberwall, Vic: Puffin Books.

Wing Jan, L. (2009). Write ways: Modelling writing forms (3rd ed.). South Melbourne, Vic: Oxford University

Monday, August 9, 2010

The Curriculum Perspective

Secondly, the inherent relationship between the three modes is articulated in the overview for each standard. At standard four, for example, the modes of speaking and listening and writing and representing support learning in the reading and viewing strand. In reading and viewing, students are required to ‘discuss the ways texts are designed to appeal to and position readers...’ (DoE, n.d., p. 59). This cannot occur unless a student engages in writing, speaking or listening, and to engage in an effective, coherent discussion, students must be competent in all of these areas. In their development of writing and representing, students adjust their communication according to purpose, context and audience (DoE, n.d., p. 60). Likewise, speaking and listening incorporates listening to texts read aloud and preparing talks and presentations, which requires reading and writing.

As I demonstrated in my last post, theorists are almost unanimous in their assertion that the modes of communication cannot be separated in the teaching of literacy. A brief look at the Tasmanian English-literacy curriculum indicates that the curriculum reflects that notion.

As I demonstrated in my last post, theorists are almost unanimous in their assertion that the modes of communication cannot be separated in the teaching of literacy. A brief look at the Tasmanian English-literacy curriculum indicates that the curriculum reflects that notion.

References:

Department of Education Tasmania Hobart , Tasmania

Sunday, August 8, 2010

Oracy: Old but not forgotten

The modes of reading and viewing, speaking and listening and writing and representing outlined in the English-literacy curriculum all contribute to the teaching and learning of English in Australian schools. I have set up this blog in order to demonstrate the relationship between these three modes of communication. In this post I will analyse the importance of the three modes in the context of the work of various literacy theorists. In the posts that follow, I will look at the three modes within the Tasmanian English-literacy curriculum, and then introduce my own teaching strategy to provide context to the discussion. Here, though, I begin with a look at oracy and its place alongside reading and writing in English teaching.

In historical societies, information was created and communicated orally, and speaking, reading and writing were considered separate skills (Kral, 2009). As development occurred, narrative structure contributed to the way people expressed ideas in conversation and writing (Rogoff as cited in Kral, 2009). As a result, oral traditions have given way to written forms of communication, and there remains some conflict concerning the place of oracy in the contemporary literacy context.

There is little argument about the importance of reading and writing in the English literacy curriculum. According to McDougall (2004), the conventional modes of reading and writing take priority over other forms of communication for teachers of English. This is because it is generally accepted that ‘a fully literate person is one who can read and write; development of this form of literacy is viewed as one of the most significant goals of education’ (Kress & van Leeuwen, as cited in McDougall, 2004, p. 113). However, oracy, or speaking and listening, is equally as important as reading and writing. Speech is the first and most significant means of communication to develop in young children. In the classroom, learning is presented and interpreted through speaking and listening, and learners must use oracy to develop communication and thinking skills before they can be effective readers and writers (Campbell & King, 2006). In its Initial Advice Paper for the National English Curriculum, the National Curriculum Board (2008) stated that:

The subject of English has historically been largely about the reading and writing of printed texts. More recently there has been debate about the growing significance of… communication such as speaking and listening, combinations of visual information with language, and the new digital developments…Clearly these forms of communication are expanding in and out of formal education, and so they have an important place in a national English curriculum. (p. 8)

This statement coincides with a growing body of theory that supports the integration of multimodal communication in literacy teaching and learning (Healy, 2006; Huijser, 2006; Kalantzis & Cope, 2001; Matthewman, Blight, Davies & Cabot, 2003; McDougall, 2004). As such, literacy teachers should recognise the equal importance of all three modes of communication in the English curriculum. This is made difficult by the national assessment programs in literacy, which emphasises the importance of reading and writing at the expense of a holistic, multimodal pedagogy (Unsworth & Chan, 2009). Over the next few posts, I will be developing a learning strategy that illustrates the interconnectedness of reading and viewing, writing and representing and speaking and listening in the English curriculum.

References:

Campbell, R., & King, N. (2006). Oracy: The cornerstone of effective teaching and learning. In R. Campbell & D. Green (Eds.), Literacies and learners: Current perspectives (3rd ed.) (pp. 84-100). Frenchs Forest , NSW: Pearson Education Australia

Healy, A. (2006). Multiliteracies: Teachers and students at work in new ways with literacy. In R. Campbell & D. Green (Eds.), Literacies and learners: Current perspectives (3rd ed.) (pp. 191-207). Frenchs Forest , NSW: Pearson Education Australia

Huijser, H. (2006). Refocusing multiliteracies for the net generation. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 2(1), 21-33.

Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2001). Introduction. In M. Kalantzis & B. Cope (Eds.), Transformations in language and learning: Perspectives on multiliteracies (pp. 9-18). Melbourne, Vic: Common Ground.

Kral, I. (2009). Oral to literate traditions: Emerging literacies in remote Aboriginal Australia. TESOL in Context, 19(2), 34-49.

Matthewman, S., Blight, A., Davies, C., & Cabot, J. (2003). What does multimodality mean for English? Creative tensions in teaching new texts and new literacies. Literacy Learning: The Middle Years, 11(1), 31-36.

McDougall, J. K. (2004). Changing mindsets: A study of Queensland Central Queensland University

National Curriculum Board (2008). National English Curriculum: Initial advice paper. Retrieved from http://www.acara.edu.au/engagement/past_papers.html.

Unsworth, L., & Chan, E. (2009). Bridging multimodal literacies and national assessment programs in literacy. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 32(3), 245-257.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)